Can We Put Tasma Pah To Sleep?

In the legend of Sinbad the Sailor, there is a story of Peer e Tasma Pah. It goes like this:

On the fifth voyage of Sinbad, he is alone on an island after a shipwreck. Wandering the island, he comes across an old, dishevelled man babbling in a language Sinbad did not comprehend. This creature was Peer e Tasma Pah. He had shoestring legs and was unable to get up and walk. He begged Sinbad to carry him on his shoulders and get him some water and food. Sinbad hoisted him up on his shoulders out of sympathy. Once Tasma Pah was seated, he tightened his legs around Sinbad’s neck, to the point of choking him. He would then not leave Sinbad for even a minute and dictate him around. It is said that Sinbad carried the old man on his shoulders for months. The dreadful monster never slept. He kicked and slapped but Sinbad could do nothing at all. It took a magical wine, Mushroob, which made the old man drowsy put him to sleep. Finally, he fell off Sinbad’s shoulders.

Are we all in the grip of a Tasma Pah? Are we being dictated and conditioned by a sinister complex, a war machine, a capitalist cartel?

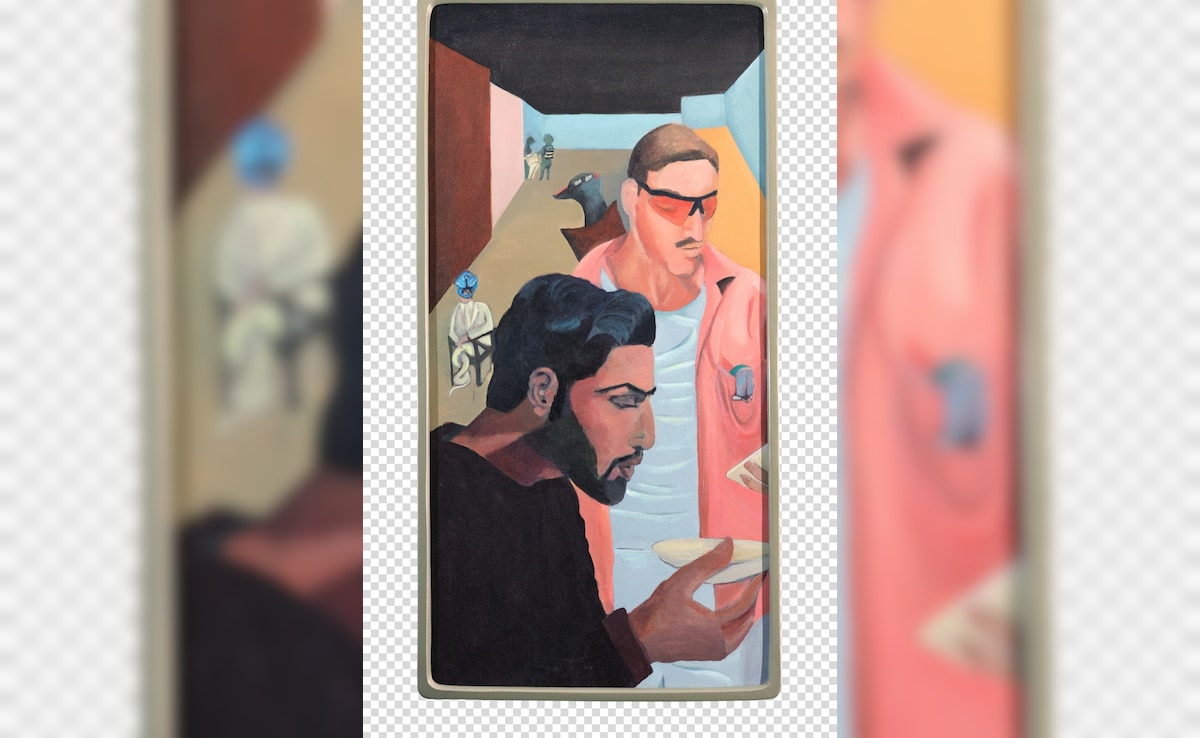

The questions race through one’s mind as one takes a walk through the dimly lit LTC gallery at Delhi’s Bikaner House. Lights focused only on a clutch of paintings that are framed like innocuous mobile screens. You feel you are looking into your phone screens. The vivid images are all too familiar.

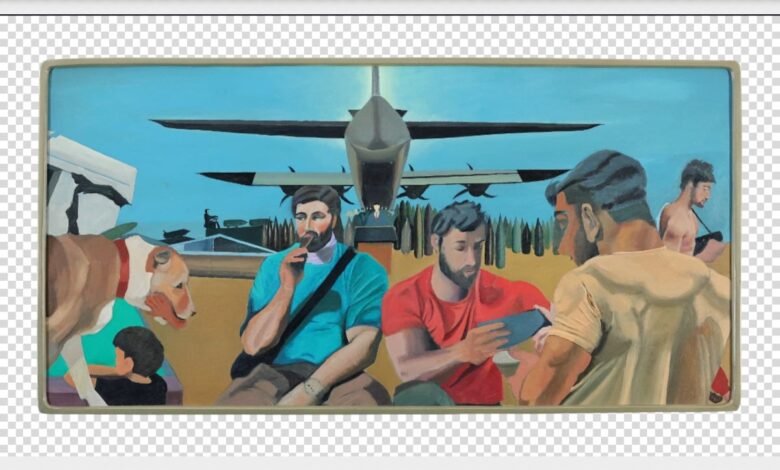

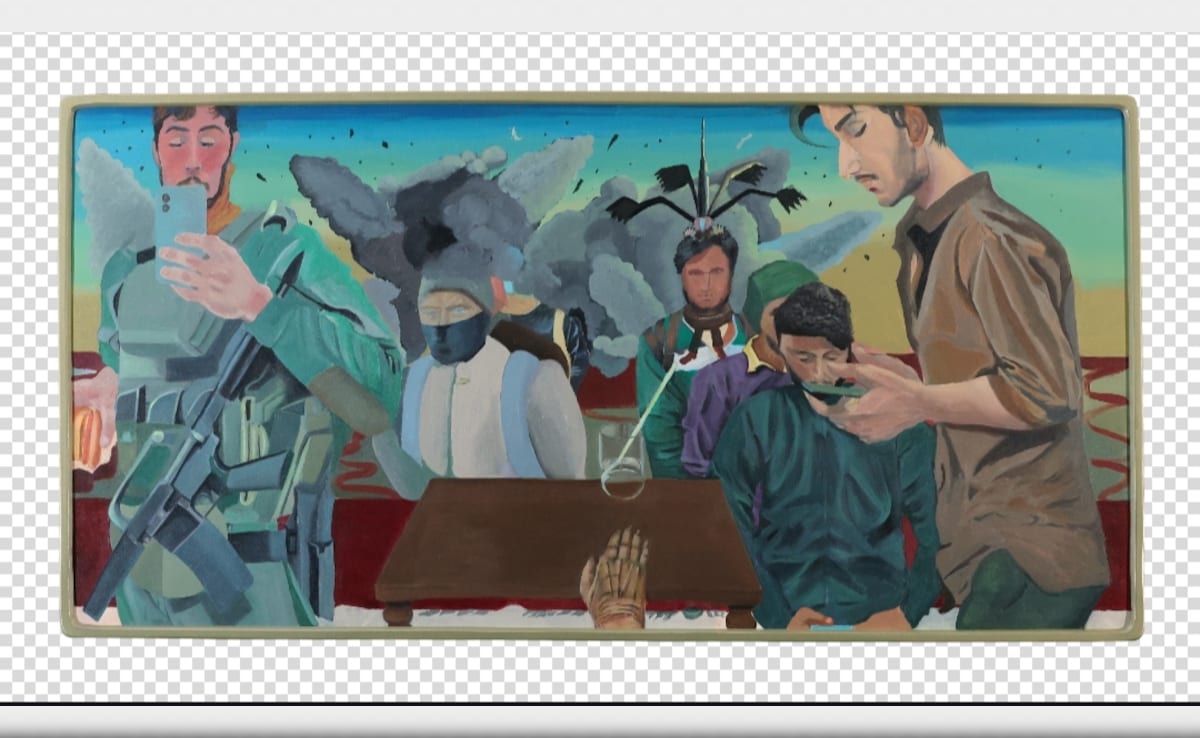

Young men wiling away their time at the tea stalls, at a maidaan, in their drawing rooms, engrossed in their smartphones. Every painting has a foreground and a background. In the foreground are young, well-built men going about their usual business. The background is war scenes, destruction, drones, missiles, bombs, soldiers. The two are separate but together. The war is no more a bad thing. It’s a spectacle that’s beamed live into our drawing rooms, on our cellphones, making us numb and immune to its horrors.

It’s like a mobile game where friends take pleasure in killing each other. Robots and fictional figures blow each other up on phone screens. Blowing up humans, razing houses, bombing schools, all look the same on the evil screen. Who has the time or attention to be shocked or to mourn? It’s all just 15-second content. The next reel or the next image will demand a different reaction or emotion. Digital decadence at its worst. Men are machines. Humans are just metadata.

Drones hover like demons in the paintings. The joystick that controls the drone is the modern-day arrow in the quiver of Paris (In The Iliad, Paris is responsible for starting the Trojan War). Modern day Paris can make a quick killing even on a holiday. The war machine has got a new toy. The drone can kill a “target” miles away. The killer sees the action on a small screen. Humans become shadowy figures on the screen. The targets. Click, boom, gone. Game over.

In another work, a young soldier gleefully posts a selfie from the warzone strutting on a little girl’s bike. He tags a caption: ‘Mother, you would be proud. Killing is fun’. The image appears on millions of phones. Killing becomes normal. No one is shocked anymore.

Years ago, the image of Aylan Kurdi washing ashore lifeless shocked the world. Now, dead and bleeding children are normal.

In the paintings, the soldiers are depicted with their necks in the grip of Tasma Pah. The ordinary men are all beefed up, straight out of the gym. Flaunting their biceps and abs in tight tees. Probably, their bodies are the only thing they control, and which give them a sense of achievement. There is pressure on everyone to look the type. And cracking it makes these young men feel they have arrived. That they belong.

Lies. Big lies.

Lie Machine, an exhibition by Moonis Ijlal, is haunting and disturbing. We just watch. We don’t speak.

“You do not even have the language to say what is happening to you?”, these words scream at you at the gallery entrance.

What is the genesis of these images?

Ijlal says: “Lie machine began with a post-midnight routine of stepping out for chai with my cousins and their friends. I saw a world is awake after dark of young men and women making reels on their phones, at times dangerously, on the side of flyovers with speeding trucks and cars whizzing past them. At the chai dhabas, student gamers played Free Fire game of guns at 2 am and some resented new social media stars gaining followers with their, mostly, sexual performances. But the men were most helpless watching reels posted from war zones. Choreographed reels of homes being bombed on camera. Or of men posing in women’s lingerie in bombed homes.”

“These all-night ghettos of the poor looked vulnerable and prone. And the reels of tonnes and tonnes of bombs reducing a city to a ‘demolition site’ left an impact we commonly felt in our minds while we watched it happening live on mobile phones elsewhere. Feeling complicit, we looked away.”

On Ijlal’s canvas, we meet ourselves. The images expose us. How we have been controlled by the war machine, the corporate greed, the beast that never rests. Our own Peer e Tasma Pah, out to suck the planet dry. But do we have our Mushroob, the magical potion that can put the demon to sleep?

(Moonis Ijlal’s solo exhibition “Lie Machine” is on at LTC gallery, Bikaner House, till February 10)

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author

Source link